Ask almost anyone in the oil industry in Libya about when oil was first discovered in the country and they will say that it was in 1958, although not in commercial quantities, and that it was the next year that the first serious discovery was made. After all, that is what searches on the internet say, so it must be true.

Except it is not true.

In a house in Rome, the home of the daughter of an extraordinary Italian explorer, proudly sits a small bottle. It contains a little of the first oil known to have been discovered in Libya. The discovery was in 1938, not 1958.

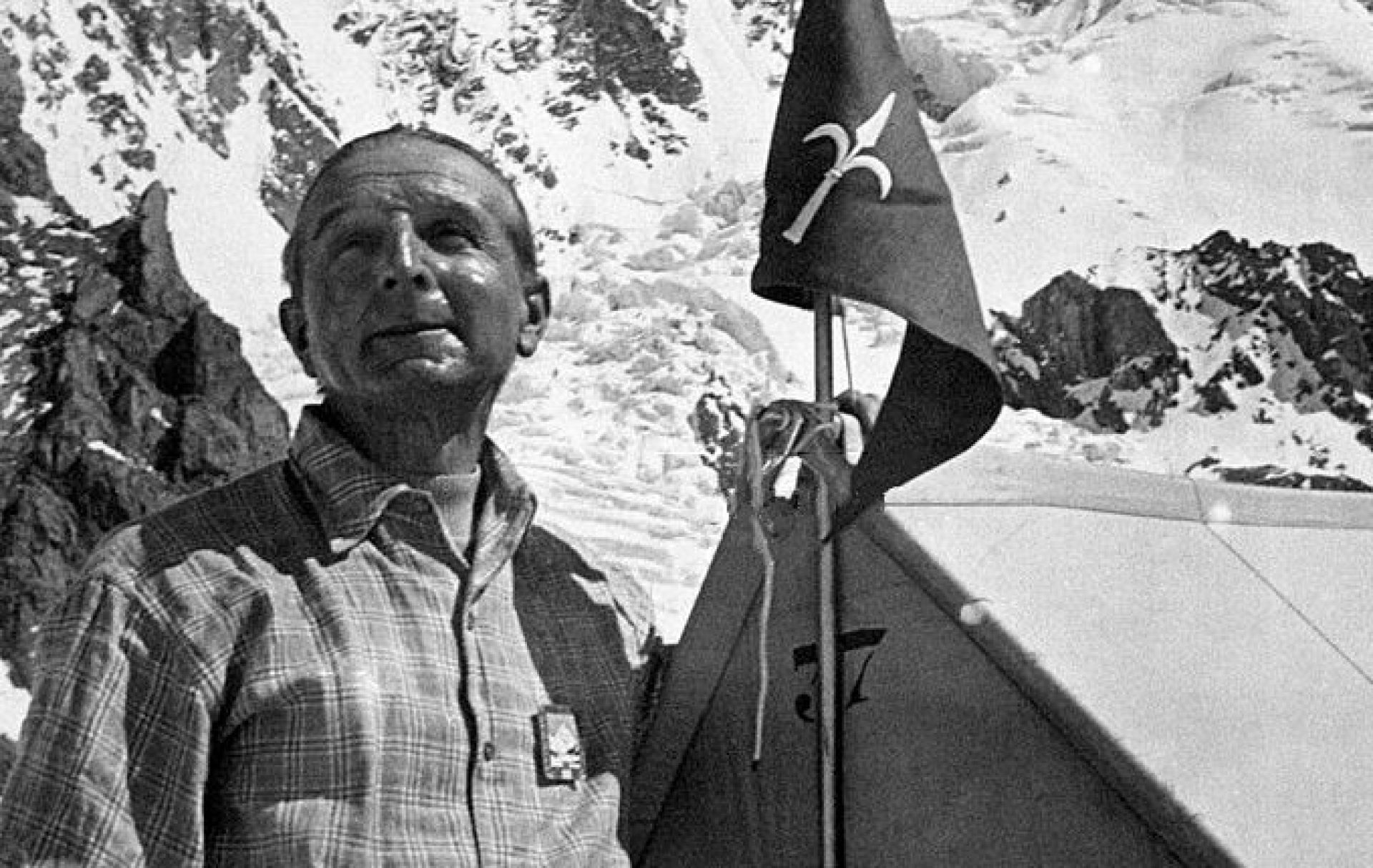

Geologist, researcher, cartographer, adventurer and mountaineer, Count Ardito Desio is largely forgotten today, but it was his feisty exploration of the Libyan interior in the 1920s and 1930s which eventually led in 1938 to his discovery of oil, which two decades later was to lay the foundations for the country’s prosperity.

Desio’s geological expeditions reached as far south as Jabal Arkenu and the Tibesti Mountains. Though sometimes sponsored by Italy’s Geological Society, he himself financed a number of his forays with camel-riding escorts to smooth his way past naturally suspicious locals. The picture that emerges is of a scientist absolutely devoted to his researches, to the extent that some of his trips deep into the country took place during the punishing Libyan summers.

His expeditions resulted in major contributions to knowledge of Saharan geology in general, of the area’s mineral and petroleum potential, and in particular, its hydrology. Indeed, Desio was one of the first researchers to document Saharan climate change at a time when this fundamental shift in the environment was still hardly even considered.

When Desio was probing the secrets of the Libya desert there were no topographic maps, no air or satellite photos, and certainly no GPS. Navigation was by compass and theodolite.

His travels took him over much of Libya, which of course was then occupied by the Italians. Between 1935 and 1936 he explored the Fezzan, from both the geological and hydrological point of view, as well as the Tibesti massif in the Central Sahara. In addition, he spent long periods travelling in Cyrenaica and to Kufra. These journeys sometime lasted months at a time.

Up until 1940 he organised and directed the Libyan Geological Survey, which included research into mining as well artesian waters.

in 1938, the same year that he discovered oil in the subsurface of Libya, he also discovered exploitable deposits of Carnallite, a source of potassium and magnesium, in the oasis of Marada along with rich artesian aquifers in some zones of northern Libya. This helped boosted the development of agriculture. However, his further explorations in this region were terminated by the outbreak of World War II which led to the end of the Italian occupation.

It is said that his discovery of oil was never followed up because it was not in viable amounts but that was never tested. The war put paid to any efforts at exploration and production.

In later years Desio was feted in Tripoli for his contributions to Saharan geology. During one of his return visits to the capital of the now independent Libya, a man introduced himself to the professor as one of a raiding party that had attempted to murder him in the desert many years before.

Desio’s geological maps and reports of the 1920- 30s formed the basis for oil exploration in Libya in the 1960s. His findings were an essential part of the database that guided the oil companies in their initial exploration. Libya’s subsequent oil wealth was thus largely based on Desio’s earlier remarkable fieldwork.

Ardito Desio was born in Palmanova, in northeast Italy, in 1897 and served as a lieutenant in the Alpine Regiment during WW1. He then studied geology at the University of Florence, before being appointed to a lectureship in Milan, subsequently being promoted to Professor and Director of the Geological Institute. His researches in Libya were dictated as much by his scientific enthusiasm and curiosity as by any loyalty to Italy. His epic travels, which over a period of some 70 years took him also to Ethiopia, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran among many other places, and in the face of considerable privation are a testimony to his doggedness. Indeed, he himself lived to be no less than 104. By the time he died in 2001 he had been able to see Libya benefit handsomely from the fruits of his extensive early researches.